I am writing an Arduino Button Library Extension (ABLE) to provide a simple, efficient, low-memory usage button library. It will support push buttons, clickable buttons and long press buttons, but the library won’t include all these features unless you need them.

If you use buttons, microswitches and similar mechanical devices in your projects, you may find when pressed (or released) the transition between open and closed is not completely clean. As the metal contacts (dis)connect, the state can “bounce around” between open and closed before stabalising.

To a program running on a micro-controller, this contact bouncing creates “noise”, producing a stream of signals interpreted as multiple presses until the signal becomes stable in its intended state. A simple loop-counting program running on the Arduino Nano can loop() approximately 289,000 times per second.

Additional circuitry could smooth these transitions, but a software-only solution is useful. This involves sampling the button signal in quick succession to ensure the signal has stabalised.

There is a Debounce LED toggle example found in the Arduino IDE under File > Examples > 02. Digital > Debounce. This uses significant program and variable memory, especially for microcontrollers with limited memory such as Arduino Nanos:

Sketch uses 1116 bytes (3%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 19 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2029 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

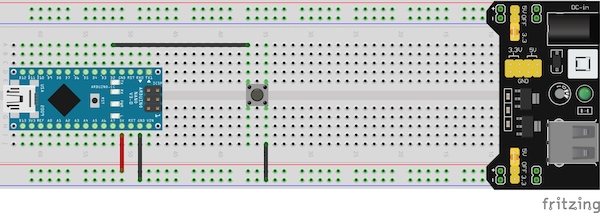

I looked at various approaches based on the Arduino sample and some internet searches. Using a simple setup of an Arduino Nano and push button connected from pin 2 to ground (using the internal pull-up resistor in the Nano), I optimised the debouncing algorithm.

In this configuration, the internal pull-up resistor of pin 2 keeps the signal HIGH when not pressed and closing the push button grounds the signal, making it LOW when pressed. Thus a digitalRead(BUTTON) returns 1 when not pressed and 0 when pressed.

Non-Debounced Button

The simplest program involves not debouncing the button. In some scenarios this might be acceptable (for example direct control of an LED instead of toggling):

#define BUTTON 2

void setup() {

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, digitalRead(BUTTON));

}

Sketch uses 890 bytes (2%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 9 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2039 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

When a button grounding pin 2 is pressed, the LED stops lighting up. This consumes a small amount of program storage and dynamic memory. I use it as a benchmark.

Setup pinMode order

Interestingly switching the order of pinMode calls in the setup() function, it costs 2 bytes of program storage:

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP);

}

Sketch uses 892 bytes (2%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 9 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2039 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

There must be a compiler optimisation available. I am not sure what at this point. It would be worth dissassembing the generated code to see. Something to investigate later (with byte vs bool types discussed below).

Non-Debounced Toggle

To illustrate the contact-bounce problem, the toggle example below fails intermittently. When working correctly, releasing the button (i.e. completing a “click”) should toggle the in-built LED. However, sometimes the LED changes during both button-press and release, or it flickers for a moment. A non-debounced button generates multiple signals toggling the button on and off with a single press:

#define BUTTON 2

bool led = false;

bool state = false;

void setup() {

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

bool reading = digitalRead(BUTTON);

// If button not pressed but was pressed.

if(reading && !state) {

led = !led;

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, led);

}

state = reading;

}

Sketch uses 910 bytes (2%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 11 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2037 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

Cleaning up Debounce

I went through the Arduino Debounce example and cleaned it up whilst keeping toggle functionality:

- I avoided the unnecessary unsigned long delay value as we’re only interested in the delta between two

millis()calls. - Since the digital pins can only be on or off, I also changed the

led,state,lastandreadingvariables tobooltypes. - Finally I combined the toggle checks into a single check.

The result is:

#define BUTTON 2

#define DELAY 50

bool led = false;

bool state = false;

bool last = false;

unsigned long debounce = 0;

void setup() {

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

bool reading = digitalRead(BUTTON);

// New reading, so start the debounce timer.

if (reading != last) {

debounce = millis();

} else if ((millis() - debounce) > DELAY) {

// Use reading if we have the same reading for > DELAY ms.

// If button not pressed but was pressed.

if(reading && !state) {

led = !led;

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, led);

}

state = reading;

}

last = reading;

}

Sketch uses 1030 bytes (3%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 16 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2032 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

Bytes vs Bools

Another currently unclear compiler optimisation worth investigation was achieved by using byte variables for state, last and reading. Using byte instead of bool types saved some program storage space:

Sketch uses 1020 bytes (3%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 16 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2032 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

Conversely, changing led to a byte variable increased program storage by 2 bytes.

Bitshift Readings

One elegant way to take multiple measurements follows an algorithm described in A Guide to Deboucing, Part 2 by The Ganssle Group.

This involves shifting pin reads into a readings variable on a regular basis. The resulting readings value is 0x00 when the last 8 readings returned the same closed state and the value 0xff when the last 8 readings were the same open state. Any other value indicates an intermediate state. Shifting a new reading in every 5ms means 8 readings every 40ms.

| Binary Readings | Meaning |

|---|---|

11111111 | Button has been open for >=40ms. |

11111110 | Last reading shows button closed… |

11110100 | Button bouncing around… |

10100000 | Button has been closed for 25ms, still might bounce around… |

10000000 | Button reads closed for 7 x 5ms cylces (35ms). Almost there… |

00000000 | Button closed for >=40ms, so can be considered stable. |

The challenge is loop() speed (remember the 289,000 loops/sec). We can’t read each time round the loop as this passes too quickly. Adding a timer guard to only read every 5ms ensures enough time passes independent of CPU speed and work done by the loop():

#define BUTTON 2

bool led = false;

byte readings = 0;

bool state = 0;

unsigned long debounce = 0;

void setup() {

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

if(millis() - debounce >= 5) {

readings = (readings << 1) | digitalRead(BUTTON);

debounce = millis();

}

// If button not pressed but was pressed.

if(readings == 0xff && !state) {

state = true;

led = !led;

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, led);

} else if(readings == 0x00) {

state = false;

}

}

Sketch uses 1040 bytes (3%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 16 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2032 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

Timing with a 4-byte unsigned long debounce value results in program storage higher than other options. Any gains with shifting readings into a readings variable is lost.

If you know the loop() speed you could count the loop calls and read at regular intervals:

#define DELAY 0xff

...

byte debounce = 0;

...

void loop() {

if(!(++debounce & DELAY)) {

readings = (readings << 1) | digitalRead(BUTTON);

}

...

Sketch uses 960 bytes (3%) of program storage space. Maximum is 30720 bytes.

Global variables use 13 bytes (0%) of dynamic memory, leaving 2035 bytes for local variables. Maximum is 2048 bytes.

The debounce variable becomes a byte or unsigned int large enough to count the loop() calls. To use part of a larger variable, you need to mask off the low-order bits using 0x1, 0x3, 0x7, 0xf, 0x1f, 0x3f, 0x7f, 0xff, 0x1ff … 0xffff etc. to test for zero. When the value becomes zero (through masking) or because it wraps round, a reading can be taken.

Another option would be to capture the readings using a TimerInterrupt callback function and process them in the loop() function. This approach is beyond the scope of this blog post. The program storage required would likely exceed guarding readings in the loop() function.

Conclusions

Debouncing is important in many situations (though not all). Even if not critical, the debounce code can be optimised to minimise additional memory overhead making it worthwhile for many situations. If memory is paramount, perhaps hardware solutions would be better.

Whilst the bit-shifting option is elegant, the main challenge is reading at regular intervals. Care should be taken not to incur additional memory requirements making the result less memory efficient than an optimised original solution.

If you can count the loops() and take readings only when the count wraps/masks to zero, this can be the most memory efficient solution. This becomes dependent on CPU speed and the amount of work performed in the loop().

The sample programs shown in this post can be found on GitHub.

Comments